Courting Racial Justice - Preview

Harry Truman Outflanks the Southern Barons of Capitol Hill

by Robert Shogan

COURTING RACIAL JUSTICE

When Franklin Roosevelt made Senator Harry Truman his vice-presidential running mate at the 1944 Democratic convention, many black Americans reacted with dismay and foreboding. “Appeasement of the South” was the charge leveled by the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s most influential black newspapers, which likened the choice to the sell-out of the infamous Munich Pact. Many blacks, and white liberals too, were suspicious of Truman’s heritage in the former slave state of Missouri. Moreover they feared that given the sixty-two-year-old Roosevelt’s faltering health, Truman’s succession to the White House was all too likely to happen.

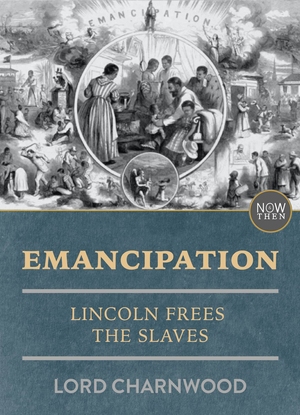

Sure enough, Roosevelt died barely four months into his fourth term, and Truman took over the Oval Office. But the new president’s performance would defy the dire expectations of blacks. Near the end of Truman’s second term, publishers of the nation’s major black newspapers presented him with a plaque that praised him for “having awakened the conscience of America” and for “his courageous efforts on behalf of freedom and equality of citizens.” The inscription was an acknowledgment of the growing recognition that Harry Truman, the nation’s thirty-third chief executive, had become the first since Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth, to do anything of consequence to redress the injustices imposed upon black Americans, and in this case long after their emancipation.

This was no easy task for Truman, largely because of the unyielding resistance of Southern legislators entrenched on Capitol Hill. But, driven by black demands and his own conscience, Truman found ways to get around the Congress. Most famously, he directed the integration of the armed forces by executive order. Lesser known but also of great importance was his use of the U.S. Justice Department, working through the courts, to reverse a half-century of rulings denying the rights of black Americans and to open the way to unprecedented advances. In dealing with the courts, instead of depending on executive orders, Truman’s lawyers wielded a more subtle but as it turned out an equally potent weapon, the amicus curiae or friend-of-the-court brief. In five Truman years the Justice Department would file a series of such briefs that would have a profound impact on the jurisprudence of civil rights, later culminating in the epochal ruling overturning school segregation.